Zanzibar Christians

A short illustrated history of the early churches of Zanzibar

1500-1800 The Portuguese.

Christianity was first introduced to Zanzibar by the Portuguese. Moving up the from the south after successfully rounding the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 they staged a violent and ultimately unsuccessful bid to lay claim to the harbors, trading routes and resources of almost 2000 miles of African coastline.

Reaching Zanzibar in 1499 thePortuguese soon established a Catholic Mission and trading station in Zanzibar Town. For the next 200 years they dominated the shipping lanes of East Africa and strived to establish a string of coastal settlements. Ruins of Portuguese settlements can still be found near Fukuchani in the north and on Pemba Island. The Fortress that stands today near the harbor in Zanzibar City was built overtop of an earlier catholic chapel located there; after it was captured by Omani forces. These forces are said to have been invited to Zanzibar and Pemba by the islanders to help drive out the overbearing Portuguese.

After decades of warfare and destruction that saw Mombasa set afire, captured or recaptured at least five times, the Portuguese retreated from Azania. Back south they went, out of reach of the incessant attacks born by the seasonal Dhow winds.

An Oasis of Tolerance

In 1841 the Omani warrior Sultan, Seyyid Said was so taken by these islands that he had helped to secure that he moved his Capital to Zanzibar. His desert upbringing seemed to motivate him to industriously develop the lush Islands. He treated Zanzibar like an Oasis of the sea. He enforced massive tree planting schemes, dug numerous wells, and built lodgings enough for hundreds of visitors. He knew that visitors would linger at an oasis. He also knew that much trading would occur if the site was well provisioned and safe. He would of course expect to get a percentage of all transactions there, in exchange for keeping it that way.

To increase trade he welcomed merchants from India to open branch offices in Zanzibar.

Due to

the British conquests in India many of these merchants were technically

British subjects. He therefore also began to welcome British officials to the

islands to represent the interests of these subjects. He soon entered into

formal trade agreements with the British and other western governments.

the British conquests in India many of these merchants were technically

British subjects. He therefore also began to welcome British officials to the

islands to represent the interests of these subjects. He soon entered into

formal trade agreements with the British and other western governments.

Trading houses were established in Stone town by American, German, French and English firms. Zanzibar harbor also offered fuel and repair services for war ships and merchant vessels. These ships brought additional influxes of westerners to Zanzibar. As another consideration for the many visitors to his oasis the Sultan allowed people of all faiths to conduct religious services as they choose.

A devout Muslim, he set an example of tolerance for the religious needs of

others while simultaneously exuding confidence in the religion of his ancestors. Overtime his successors

followed this pattern, allowing the establishment of

several Hindu

Temples, two Cathedrals, one each for Catholics and Protestants, a Zoroastrian Funerary and

Mosques for every major and minor branch of Islam, all within the same City.

A devout Muslim, he set an example of tolerance for the religious needs of

others while simultaneously exuding confidence in the religion of his ancestors. Overtime his successors

followed this pattern, allowing the establishment of

several Hindu

Temples, two Cathedrals, one each for Catholics and Protestants, a Zoroastrian Funerary and

Mosques for every major and minor branch of Islam, all within the same City.

1800 -1900 Catholics, Quakers and the UMCA.

After the Portuguese retreat only a few Goan Christians

remained on

Zanzibar. They had no church but maintained their community through private

devotions. Later in the 1800's the influx of westerners began to include the

occasional passing missionary and clergy from ships in the harbor. In 1844 more

permanent Christian missionaries arrived in East Africa in the form of the

Lutheran minister Joseph Krapf and two companions who were working for the

English Church Missionary Society. Based in Mombasa, they visited Zanzibar and

over the next few years produced an excellent Kiswahili dictionary but they

never did establish a church in the Islands.

remained on

Zanzibar. They had no church but maintained their community through private

devotions. Later in the 1800's the influx of westerners began to include the

occasional passing missionary and clergy from ships in the harbor. In 1844 more

permanent Christian missionaries arrived in East Africa in the form of the

Lutheran minister Joseph Krapf and two companions who were working for the

English Church Missionary Society. Based in Mombasa, they visited Zanzibar and

over the next few years produced an excellent Kiswahili dictionary but they

never did establish a church in the Islands.

The

growing anti-slavery movement in Britain encouraged more Christian missionary fervor; spurred most famously by the speech David Livingston gave in 1857

appealing for England to send missionaries, workmen and poor relations to

Africa. He preached that the end of slavery could come only through "commerce

and Christianity." Livingston himself later spent many days on Zanzibar, where

he was given the use of a house by the Sultan.

fervor; spurred most famously by the speech David Livingston gave in 1857

appealing for England to send missionaries, workmen and poor relations to

Africa. He preached that the end of slavery could come only through "commerce

and Christianity." Livingston himself later spent many days on Zanzibar, where

he was given the use of a house by the Sultan.

His speeches lead to the creation to the Universities Mission to Central Africa. The UMCA was a collaboration between the faculty and alumni of Oxford and Cambridge universities, who were soon joined by enthusiasts from the universities of Durham and Dublin. In 1860 they elected Charles Mackenzie as "Bishop of Central Africa" and by October of that year he was on his way there.

The UMCA's intent was to bring Christianity to the multitude of souls living in central Africa, around lake Nyasa which Livingston had so eloquently described. To that end, after reaching South Africa, Bishop Mackenzie and companions traveled by boat up the Zambezi river and then up the Shire river to set up the first UMCA Mission in Africa at a place named Magomero.

While this Mission and it's location certainly corresponded to the name and spirit of it's Parent organization it was a momentous failure for that group. Illness and famine plagued the early missionaries and lead to the death of the Bishop. Too far from supply and communication centers, too unhealthy for those not well acclimatized and too politically unstable, the site had to be abandoned within 3 years. The new Bishop, George Tozer, first tried moving the Mission 200 miles down river to a more elevated location but that site too soon proved unhealthy and was abandoned within months.

Determined not to repeat their mistakes the UMCA leaders looked to the next likely spot from which to reach out to the heart of Africa. Madagascar was considered, as was the Island of Johanna and locations on the South African coast but Zanzibar won out in the end due to it's fine communication networks, well know food supplies and a good labor pool. The UMCA survivors therefore landed in Zanzibar on August 31, 1864.

Upon arrival they were greeted by French Catholic Missionaries. The Catholics

had

preceded the English missionaries arrival at Zanzibar by almost fouryears.In September 1860 the powerful French religious figure

Abbe Favat had

secured an agreement from Seyyid Said's successor to allow him to

move his headquarters from Reunion Island to Zanzibar.By December his

group of "two secular

priests and six nuns, ("Filles de Marie") were living near Shangani point in

a large convent house which also had a small chapel. This "convent building"

is said to have been constructed in 1860 but this construction may have in fact

been an extensive renovation of a pre-existing house. The chapel in this house

was the first church established in Zanzibar in over 200 years.

Upon arrival they were greeted by French Catholic Missionaries. The Catholics

had

preceded the English missionaries arrival at Zanzibar by almost fouryears.In September 1860 the powerful French religious figure

Abbe Favat had

secured an agreement from Seyyid Said's successor to allow him to

move his headquarters from Reunion Island to Zanzibar.By December his

group of "two secular

priests and six nuns, ("Filles de Marie") were living near Shangani point in

a large convent house which also had a small chapel. This "convent building"

is said to have been constructed in 1860 but this construction may have in fact

been an extensive renovation of a pre-existing house. The chapel in this house

was the first church established in Zanzibar in over 200 years.

The permission, given by Sultan Majid, for these French citizens to set up shop in Zanzibar, has been described asan effort by the Sultan to "offset the dominate British position by welcoming citizens of their principal European rival." If competitive political considerations were the cause of bringing together the two Christian missionary branches in one place these did not seem to result in any real friction between the missionaries themselves. Their rapprochement may have been aided by the fact the UMCA Anglicans were "high Church" men with strong Anglo-Catholic leanings.

The French missionaries were

also anxious to

avoid any trouble on Zanzibar. "Recognizing the realities of life in

Muslim Zanzibar, the Frenchmen, from about 1862, members of the Holy Ghost

Order, limited their activities to education, pastoral work amoung the city's

small Roman Catholic Goan community, and health care, opening the sultanate's

first European-directed hospital. They gained, thereby, a very favorable niche

in Arab opinion."

The French missionaries were

also anxious to

avoid any trouble on Zanzibar. "Recognizing the realities of life in

Muslim Zanzibar, the Frenchmen, from about 1862, members of the Holy Ghost

Order, limited their activities to education, pastoral work amoung the city's

small Roman Catholic Goan community, and health care, opening the sultanate's

first European-directed hospital. They gained, thereby, a very favorable niche

in Arab opinion."

Despite the hospitality of the Zanzibari people, few

Islanders had any interest in converting to the faith of the new visitors.

The

catholic missionaries understood this but also believed the real mother load of

potential converts lay just a short distance across the Zanzibar channel, on

the

mainland. They set up a small mission in

The

catholic missionaries understood this but also believed the real mother load of

potential converts lay just a short distance across the Zanzibar channel, on

the

mainland. They set up a small mission in Bagamoyo on the mainland coast in 1868

and for the most part used their Zanzibar facilities as the headquarters from

which to direct their expanding mainland

efforts. This effort included building another "French Hospital" in Bagamoyo.

Bagamoyo on the mainland coast in 1868

and for the most part used their Zanzibar facilities as the headquarters from

which to direct their expanding mainland

efforts. This effort included building another "French Hospital" in Bagamoyo.

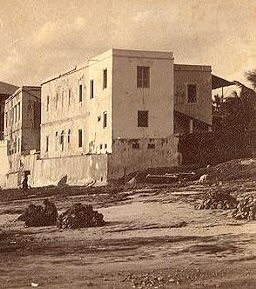

The "French Hospital" on Zanzibar was constructed just

adjacent to the convent building. This hospital was competed and in operation by

about 1890. During that time the Catholics continued to enjoy good relations

with their Zanzibar neighbors, gaining permission to build the stately Cathedral

of Saint Joseph in 1894. The cornerstone for this Cathedral was laid on July 10,

1896. The first mass was celebrated in the new Cathedral by Bishop Allgeyer, on

Christmas night in 1898.

Cathedral

of Saint Joseph in 1894. The cornerstone for this Cathedral was laid on July 10,

1896. The first mass was celebrated in the new Cathedral by Bishop Allgeyer, on

Christmas night in 1898.

Over time the Hospital on Zanzibar became less essential

and the building there was converted to a school. This was the

St Joseph's Convent

School.

Over time the Hospital on Zanzibar became less essential

and the building there was converted to a school. This was the

St Joseph's Convent

School.

The UMCA Missionaries were not idle during this time.

Living first in the Mambo Msiige House, on Shangani point, not far from the French mission, the

industrious British soon launched into a building boom of impressive size and variety. First they purchased some farm

land in a suburb named Kiungani. By 1866

construction was underway there for a building to be used as a "hostel for

released slave boys." Nearby a cemetery was laid out, that today still

contains the remains of some of the early Christians on Zanzibar.

building boom of impressive size and variety. First they purchased some farm

land in a suburb named Kiungani. By 1866

construction was underway there for a building to be used as a "hostel for

released slave boys." Nearby a cemetery was laid out, that today still

contains the remains of some of the early Christians on Zanzibar.

Next, in 1873 a second land purchase was made, this time near the center of town, almost a full city block that had been an old market square, where slaves were once sold. The call soon went out for funds to help build a church on the very site where such evil had occurred. This was the start for Christ Church Cathedral.

The following year the third and final early UMCA property purchase occurred with the securing of a track of farm land south of town near the sea, at a place named Mbweni.

The UMCA missionaries set about filling their new

properties with a variety of religious and secular buildings. At Mbweni, in 1882

they started construction of the St. John's Parrish Church. Nearby they

established a village and small farm plots for ex-slaves and built the "Kilimani

Little Boy's Home," later to become a girls school. Also at Mbweni they built a

number of vocational workshops for training converts in useful skills and

finally the St. Mark's Theological College, which later was moved to Kiungani.

The UMCA missionaries set about filling their new

properties with a variety of religious and secular buildings. At Mbweni, in 1882

they started construction of the St. John's Parrish Church. Nearby they

established a village and small farm plots for ex-slaves and built the "Kilimani

Little Boy's Home," later to become a girls school. Also at Mbweni they built a

number of vocational workshops for training converts in useful skills and

finally the St. Mark's Theological College, which later was moved to Kiungani.

Back in town, the cornerstone of the UMCA Cathedral was

laid on Christmas day 1873. The old

market square soon began to fill with other

UMCA buildings. The "Mkunzini House" was constructed in 1875 and the church soon

moved its headquarters from Mambo Msiige to that

market square soon began to fill with other

UMCA buildings. The "Mkunzini House" was constructed in 1875 and the church soon

moved its headquarters from Mambo Msiige to that location. A

dispensary was

established in 1877, eventually to become a full service hospital in 1893. A

house for the Archdeacon and one for the Bishop were built in the square as was

St. Monica's School. That building is still in use today as St. Monica's hostel.

location. A

dispensary was

established in 1877, eventually to become a full service hospital in 1893. A

house for the Archdeacon and one for the Bishop were built in the square as was

St. Monica's School. That building is still in use today as St. Monica's hostel.

The most monumental of all this work was surely Christ Church Cathedral. Essentially an amateur project personally supervised by the third UMCA Bishop, Edward Steere, it remains one of the most impressive examples of the early Christian architecture in Africa.

While

it's location was glamorized in the religious press,

While

it's location was glamorized in the religious press, it's proximity to the odorous tidal creek caused some to question it's effects

on the missionaries health. The creek that was depicted as something akin to a

Venetian canal in church illustrations was in reality more of a stinking swamp

at low tide. It was not until the creek was covered over by a road in the 30's

that the site was freed from the noxious fumes that on still days rose up around

it with tidal regularity.

it's proximity to the odorous tidal creek caused some to question it's effects

on the missionaries health. The creek that was depicted as something akin to a

Venetian canal in church illustrations was in reality more of a stinking swamp

at low tide. It was not until the creek was covered over by a road in the 30's

that the site was freed from the noxious fumes that on still days rose up around

it with tidal regularity.

The personal nature of Dr. Steer's involvement in the

construction can be seen in the many on- site

changes he had to make to the plans that were sent out from England and from the

fate of the granite columns that stand near the back of the nave. These columns were set at a time when the

Bishop was unavailable to supervise the work, having traveled to the mainland

on church business. The workmen set

site

changes he had to make to the plans that were sent out from England and from the

fate of the granite columns that stand near the back of the nave. These columns were set at a time when the

Bishop was unavailable to supervise the work, having traveled to the mainland

on church business. The workmen set them firmly and precisely vertical, just as

they had been trained to do by the Bishop, but they placed them upside down.

Upon his return the Bishop looked them over and determined that even inverted

they would bear the load, so wanting to press on with the work, he left them

just as they stand today.

them firmly and precisely vertical, just as

they had been trained to do by the Bishop, but they placed them upside down.

Upon his return the Bishop looked them over and determined that even inverted

they would bear the load, so wanting to press on with the work, he left them

just as they stand today.

The real Jewell of his architectural effort is the

Cathedral roof. Having had some prior unhappy experiences in trying to repair the

rotten roof of his old church in England, Bishop Steere was determined to build a

roof for the ages. Distrusting wood because of termites and fire danger and

having no funds for expensive iron roofing materials he decided to build

his roof out of concrete.

The real Jewell of his architectural effort is the

Cathedral roof. Having had some prior unhappy experiences in trying to repair the

rotten roof of his old church in England, Bishop Steere was determined to build a

roof for the ages. Distrusting wood because of termites and fire danger and

having no funds for expensive iron roofing materials he decided to build

his roof out of concrete.

Working

with local materials he mixed cement and crushed coral at the site in an effort to build a massive elevated vault that could span

28.5 feet. To this end he had a single pair of centering frameworks made in

England and shipped to him in pieces. This frame was setup at the construction

site with small wheels attached so that it could be "rolled along from end to

end as each piece of the roof was finished."

Working

with local materials he mixed cement and crushed coral at the site in an effort to build a massive elevated vault that could span

28.5 feet. To this end he had a single pair of centering frameworks made in

England and shipped to him in pieces. This frame was setup at the construction

site with small wheels attached so that it could be "rolled along from end to

end as each piece of the roof was finished." When it was time for the supports to be removed a large crowd gathered.

They were breathless as the scaffolding was knocked away, then left astonished

and a little disappointed when nothing happened. The roof they all had expected to

crash down has held up now for over 100 years.

When it was time for the supports to be removed a large crowd gathered.

They were breathless as the scaffolding was knocked away, then left astonished

and a little disappointed when nothing happened. The roof they all had expected to

crash down has held up now for over 100 years.

The Sultan, who by then was

Seyyid Barghash, was so

impressed that he donated a large clock; to adorn the bell tower planed for the

southwest corner of the structure. Unfortunately there was no clock in the

original plans. The politically astute decision to accept and install the

Sultan's gift lead to modifications of the tower, to make it thinner and taller.

The Sultan, who by then was

Seyyid Barghash, was so

impressed that he donated a large clock; to adorn the bell tower planed for the

southwest corner of the structure. Unfortunately there was no clock in the

original plans. The politically astute decision to accept and install the

Sultan's gift lead to modifications of the tower, to make it thinner and taller.

That in turn affected another gift,

a fine set of 25 bells, carillon chimes which together could play lengthy tunes.

However their size and weight

were clearly too much for the slender tower. Only 13 were installed, the rest of

the bells being distributed to other churches and schools.

That in turn affected another gift,

a fine set of 25 bells, carillon chimes which together could play lengthy tunes.

However their size and weight

were clearly too much for the slender tower. Only 13 were installed, the rest of

the bells being distributed to other churches and schools.

While all this activity was occurring on the main Island,

missionaries from the the Religious Society of Friends, the Quakers, had taken

up residence on nearby Pemba Island. Quakers had first reached Zanzibar as early

as 1865, when they came as employees of the western trading firms. However it was not

until Jan. 20,1897 that the first permanent Quaker mission was started at Banani

which is near the mouth of Chake Chake bay on the western coast of Pemba.

While all this activity was occurring on the main Island,

missionaries from the the Religious Society of Friends, the Quakers, had taken

up residence on nearby Pemba Island. Quakers had first reached Zanzibar as early

as 1865, when they came as employees of the western trading firms. However it was not

until Jan. 20,1897 that the first permanent Quaker mission was started at Banani

which is near the mouth of Chake Chake bay on the western coast of Pemba.

Like the UMCA, the catalyst and the funds for the Pemba

Mission came from the anti-slavery sentiments; shared by every Quaker. By then

Slavery had been officially banned on the islands but the lives of many

ex-slaves went on unchanged. For those who had left their former owner's

property there was much concern about them being homeless and whispered fears

about lawless bands roaming the countryside.

Like the UMCA, the catalyst and the funds for the Pemba

Mission came from the anti-slavery sentiments; shared by every Quaker. By then

Slavery had been officially banned on the islands but the lives of many

ex-slaves went on unchanged. For those who had left their former owner's

property there was much concern about them being homeless and whispered fears

about lawless bands roaming the countryside.

The Quaker Mission therefore was to

be an "Industrial Mission" where freed slaves could work and learn a trade.

The Quaker Mission therefore was to

be an "Industrial Mission" where freed slaves could work and learn a trade.

Theodore Burtt their leader, without ever seeing Pemba, had spoken out at the

meeting house in England saying it "be right for him to take up a plantation

in the island, and prove to the world that the freed men will work honestly and

perseveringly for their living."

Theodore Burtt their leader, without ever seeing Pemba, had spoken out at the

meeting house in England saying it "be right for him to take up a plantation

in the island, and prove to the world that the freed men will work honestly and

perseveringly for their living."

He too believed that commerce and Christianity was the path to enlightenment.

Slaves and Converts

The

Quaker Mission on Pemba was the latest in a string of "Freetown's" set up in

East Africa by Christians for the settlement of freed slaves. For years the

Royal Navy had regularly deposited the cargo of slave ships captured on the high

seas at the UMCA Mission. These newly free people were fertile soil for

proselytizing and most quickly became Christian converts.

The

Quaker Mission on Pemba was the latest in a string of "Freetown's" set up in

East Africa by Christians for the settlement of freed slaves. For years the

Royal Navy had regularly deposited the cargo of slave ships captured on the high

seas at the UMCA Mission. These newly free people were fertile soil for

proselytizing and most quickly became Christian converts.

However their increasing numbers and the complexity of their needs tried both the resources and the patience of their benefactors. Looking at the demographics the missionaries soon realized that only by developing a base of African Clergy could they hope to serve the thousands of African Christians they longed for.

Both Catholics and Protestants on Zanzibar therefore made efforts to include their local congregation in church affairs and both stove to identify and train likely candidates for religious orders.

On Zanzibar the most sustained of these efforts was at Kiungani. Where first the "hostel for released slave boys," then "St. Andrew's Teaching Training College" then the " Theological College" each in turn on this site, endeavored to educate and evaluate scores of African youths. As many as 50 students at a time lived and studied Kiungani. The curriculum stressed discipline, knowledge, faith and sports. The good students became teachers, the best students became Priests.

One

interesting fact about the sports organized for the Kiungani students is that

they featured some of the very first integrated team

competitions in Africa. The School team would often play

against groups of European Sailors from the ships in the

Harbor. Cricket was introduced first but soccer was the game for which real

crowds would gather. It has been suggested that the church embraced these games

as a tool to help teach Africans the 'modern virtues' of organization, rule

following, time measurement, teamwork and the

cooperation with officials. The Zanzibari students did take to these games with

great zeal and their football skills garnered notes of surprise and

consternation amoung their opponents. But perhaps the most memorable lesson

they gained was that they could be successful no matter what the game.

One

interesting fact about the sports organized for the Kiungani students is that

they featured some of the very first integrated team

competitions in Africa. The School team would often play

against groups of European Sailors from the ships in the

Harbor. Cricket was introduced first but soccer was the game for which real

crowds would gather. It has been suggested that the church embraced these games

as a tool to help teach Africans the 'modern virtues' of organization, rule

following, time measurement, teamwork and the

cooperation with officials. The Zanzibari students did take to these games with

great zeal and their football skills garnered notes of surprise and

consternation amoung their opponents. But perhaps the most memorable lesson

they gained was that they could be successful no matter what the game.

In 1963 the Government of Zanzibar released a stamp to commemorate the long history of religious tolerance on Zanzibar.

This stamp pictures, from left to right;

The Cathedral of Saint

Joseph, The Christ Church Cathedral

The Malindi Mosque, The

Hujjatul Islam Mosque, A Hindu Temple

Compiled and edited byTorrence Royer 2006.

All rights reserved.

For more information about the early missionaries on Zanzibar I recommend a new book titled "Zanzibar, May Allen and the East African Slave Trade," by Yoland Brown.

May Allen was the first UMCA Nurse on Zanzibar, arriving in 1875 and serving for 12 years there, mostly at Mkunzini. Her story, told through her letters home, captures the spirit and determination of these early pioneers. The book is well researched and well written, an excellent record of an almost forgotten history.

For more information contact the author at: www.eleventowns.com

A new site dedicated to supporting the Zanzibar Anglican Cathedral and raising fund for urgent roof repairs has been established.

It can be viewed at: www.zanzibarfriends.org