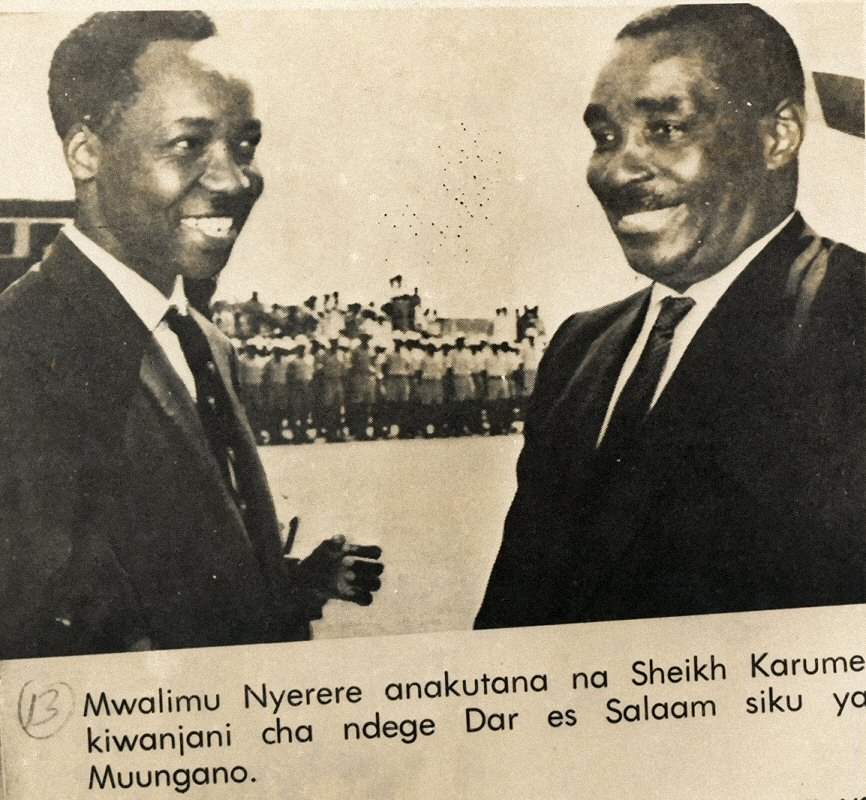

Zanzibar Courage

A longer look at the Shortest War

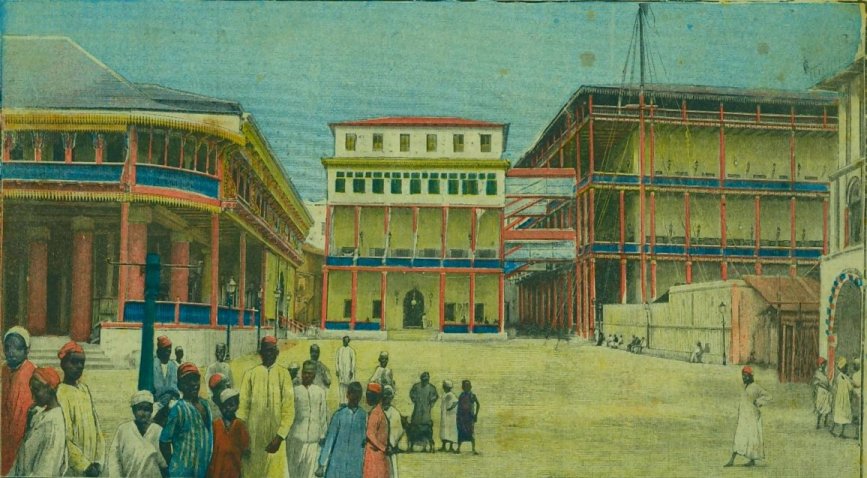

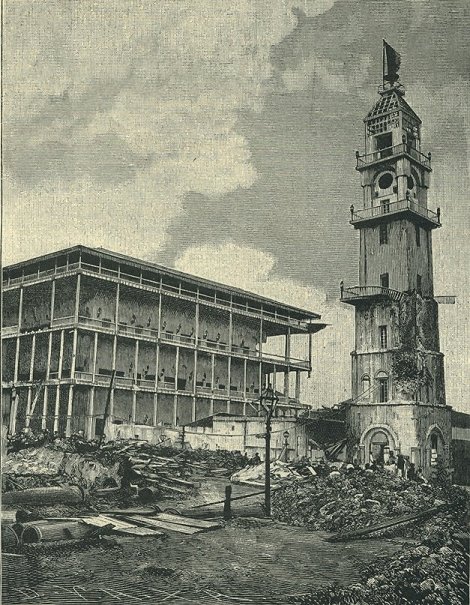

Zanzibar Palace 1896, (center) Harem building (left) and House of Wonders (right)

Introduction:

Thewar in 1896 between Zanzibar and Great Britain has been recorded as history's shortest and is often dismissed as a sort of comic-opera event not worthy of serious study. The story of this war however can reveal enduring lessons, and its small scale can actually help bring focus to some of the larger issues present whenever political violence occurs.

Zanzibar has been conquered many times in its history, but time after time the local population would reassert themselves. Tranquility would prevail only when the people felt they could engage the rulers in a meaningful dialogue about how they were to be ruled and even have a say about who should be among the leading personalities in Zanzibar. These values clashed with the" manifest destiny" values of Imperial Britain of that time. Somehow in that very brief clash, Zanzibar managed to send her cry for self-determination echoing through history. Despite the crescendo of the violence that stilled so many Zanzibari voices, the message can still be heard today if you listen closely.

The Setting:

Just before noon on August 25, 1896 Seyyid Hamid bin Thuwain bin Said, Sultan of Zanzibar, Pemba, Mafia, Lamu and all of "Syidi" (the mainland "coastal strip"), died. His death started an immediate struggle for the throne among the leading families of Zanzibar.

The Omani settlers, including the Royal family and the other prominent family/clans had a long history of self determination when it came to selecting a new ruler.

This tradition was rooted in the inter-clan consensus building process thatdeveloped around the selection of a Imam in the old country (Oman). As far back as the year 751the Imam was "elected" by clan elders. This consensus/selection process was a remarkably early example of a somewhatmore egalitarian system in an age of Despots.

The Zanzibari political succession process that was extrapolated from these earlier religious election practices could be spiced with a good deal of blood and swash. Competition amongthe leading personalities of the strongestcoalitions might be fierce.In 1859 the system was described as; "All male heirs were equally eligible for the succession... might, coupled with the election by the Tribe, is the only right." Sultan Barghash, when asked about Zanzibari succession practices put it succinctly by saying the right to inherit the crown fell to the contender with "the longest sword".

The

contender with the longest sword when Sayyid Hamid died was clearlyKhalid

bin Barghash. A young man of 29, he had the backing of the majority of the local business

leaders and the large land holders. He was acceptable to the indigenous WaHamadi and

WaTumbatu populations and he was a son of nobility. He was not however acceptable to the British.

Their man was Hamoud bin Mohamed, a nephew of the ex-Sultan of Oman and a man much interested in modern ways. The British believed he would be easier to work with than the independent minded Khalid.

The Zanzibari families however saw this blatant interference in the succession as an affront to their dignity and their traditional rights. Khalid was after all a grandson of the founding father of the Country, Sayyid Said. He had passed muster with the clans. He had the loyalty of the largest military forceon the island and by 4:00 pm on that Tuesdayhe fulfilled the final tests of inheritance, he occupied the palace and took control of the harbor, the dhow fleet and the most of the capital city.

The British were furious. They began to prepare for war. There were already

two

Royal Navy warships at anchor in the harbor when the old Sultan died. The

British government ordered their top Admiral in the Indian Ocean to hurry to

Zanzibar with his flagship and two other nearby warships were vectored towards the Islands with

orders to arrive as soon as possible.

The British were furious. They began to prepare for war. There were already

two

Royal Navy warships at anchor in the harbor when the old Sultan died. The

British government ordered their top Admiral in the Indian Ocean to hurry to

Zanzibar with his flagship and two other nearby warships were vectored towards the Islands with

orders to arrive as soon as possible.

That order went out on the evening of August 25th, the Zanzibari men at the Palace compound had the next 40 hours to contemplate their fates. Was it to be fight or flight? Would they stay? Would they respond to Khalids call to wait there and just stare resolutely into the eyes of the huge Imperial Lion that was gathering itself to leap upon them?

The Forces:

The Usurpers

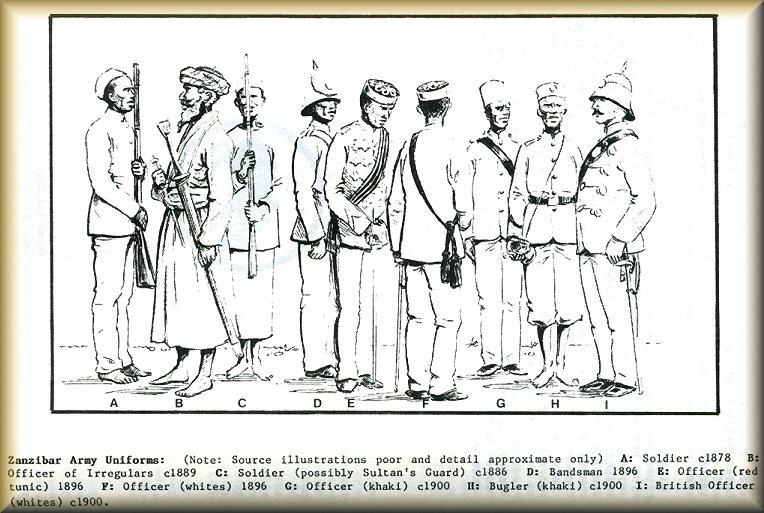

In

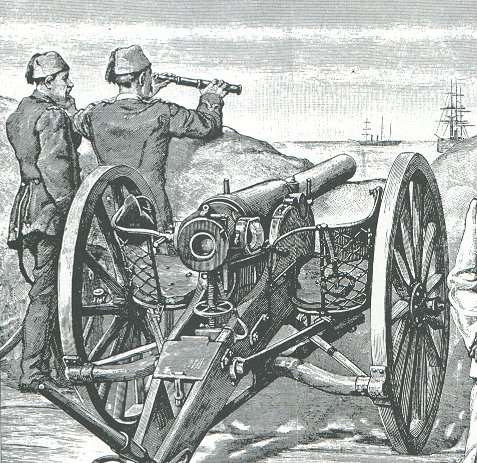

the City the Zanzibari forces were split. The old Sultan had a palace guard that

had been considerably strengthened and re-equipped over the last few years of

his reign. These now crack companies were supplemented by artillery detachments

manned by Zanzibari, Arab, Baluchi and Persian gunners (and also possibly some

Egyptian artillerymen). Altogether this Royal Guardtotaled almost 1000 troops.

In

the City the Zanzibari forces were split. The old Sultan had a palace guard that

had been considerably strengthened and re-equipped over the last few years of

his reign. These now crack companies were supplemented by artillery detachments

manned by Zanzibari, Arab, Baluchi and Persian gunners (and also possibly some

Egyptian artillerymen). Altogether this Royal Guardtotaled almost 1000 troops.

This force, to a man, went over to Khalid when the struggle for succession began. In addition, Khalid brought with him about 300 organized and armed retainers when he occupied the palace. Once he held the palace and the British demands became known an additional 1,500 Zanzibari irregulars flocked to his colors. This resulted in a total force of about 2,800 troops. These men set to fortifying the Place, the Harem building next to it and the square on the seaward frontage of this compound.

The Zanzibar Navy, whose war Dhows long had once dominated the East African coast, had by this time been sold off or converted to merchant use. The British Navy had taken over the role of policing of the Indian Ocean. However one showpiece "Steam War Yacht"had been purchased as a Sultanic Flagship and this vessel, the H.H.S. Glasgow (named after its shipyard), lay anchored in the Harbor. The crew of the Glasgow swore allegiance to Sayyid Khalid as their new Sultan and fired a salute from their elderly but sizable cannons.

The Government troops

Mathews had drilled his troops well and they had demonstrated discipline and a fighting spirit during the occasional punitive expeditions on the coast which they undertook at the behest of the government (and/or the British Resident). They were however primarily an infantry force with no heavy guns.

There

were also serious concerns among the British diplomats as to the loyalty to

these "loyalist troops" and in truth they showed little sympathy forthe British

meddling. However they were professionals and Mathews correctly asserted that

'his' men would follow

any orders he gave them.

There

were also serious concerns among the British diplomats as to the loyalty to

these "loyalist troops" and in truth they showed little sympathy forthe British

meddling. However they were professionals and Mathews correctly asserted that

'his' men would follow

any orders he gave them.

The diplomats however decided they would feel safest and believed they would have a better grip on these troops, by deploying them in defensive positions, well south of the Palace, around the diplomatic quarter of the city.

The Royal Navy

Anchored in the Harbor at the time of the old Sultans death were the British Light Cruiser H.M.S. Philomel and the gunboat H.M.S. Thrush. They were joined by the Thrush's sister ship, the H.M.S. Sparrow at 5:30 pm. Laterthat same Tuesday evening the governmenttroops in town were reinforced by contingents of British marines landed from these ships. The marines brought with them some naval gunners, at least one field piece and twolarge machineguns (Maxim guns). Thesewere promptly entrenched around the British Embassy.

Then the additional naval forces also began to assemble. Next to appear at about 9:00 in the morning on Wednesday was the larger Cruiser H.M.S. Raccoon and then at mid day on August 26, 1896 the huge Flagship H.M.S. St. George dropped anchor in Zanzibar Harbor.

Together these five vessels mounted 78 major guns of seven different classes, ranging in size from 3-pounder cannons to 9.2 in. precision rifled guns.

- 20,3 pdr. cannons

- 12,6 pdr. ''

- 8,9 pdr. ''

- 12,4 in guns

- 8,4.7 in ''

- 16,6.0 in''

- 2,9.2 in ''

These ships also carried many heavy machine guns and each had several small gigs and launches by which the scores of marines they carried could be landed. The ships moved in-shore, maneuvering very close to the fortified compound. The H.M.S. Sparrow ended that second day of the confrontation anchored directly in front of the Palace, the H.M.S. Thrush was just a bit to the north but even closer to the shore, a mere 200 yards from the sea wall.

All in all this was the most formidable force ever assembled to that time in East Africa.

Existential Moments:

The Zanzibari response to this marshaling of forceswas continued defiance on the one hand and diplomatic maneuvering on the other. The British issued a written ultimatum. Sultan Khalid was told that he must quit the palace and disperse his forces or the British would attack. He was further advised by the British that"having usurped the Sultanate of Zanzibar without consulting the Protecting Power"he had "committed an act of open rebellion against the government of her Britannic Majesty." The British then refused to negotiate and would not communicate further with the "rebel forces".

Sayyid Khalid replied that he would not attack the Europeans and wished only for peace between them. However he also said that he could not abandon the Palace, "his house and the house of his father." He contactedthe French, American and German governments to seek their intercession. All refused; these countries each had treaty agreements with the British that in one way or another deferred to the Brits on all matters within'their' protectorate. The Sultan asked the American Ambassador to deliver a message to the English Queen. It read: "Queen Victoria, London. Hamed bin Thweni is dead. I have succeeded to the throne of my forefathers. I hope friendly relations will continue as before. Khalid bin Barghash, Sultan." This message was never delivered.

Some have suggested that these efforts to engage in a long distance (and no doubt lengthy) diplomatic campaign indicates that the Zanzibari were unaware of their immediate risks and were foolish in not realizing how lethal the British guns were and how willing the Navy was to use them.

This is clearly wrong. There can be no doubt that the Zanzibari leadership

knew exactly how lethal the British forces could be. Since as far back

as his Grandfathers' reign some of Khalid's Ministers had traveled to

Europe and visited the massive armament factories of the Industrial revolution.

They alsohad among themselves years of experience with naval gunnery and

had watched the recent British military operations in the Indian Ocean with a keen eye.

In regard to the seriousness of British threats, they had to know that the British showed no compunction about the use of force in these waters against those who opposed them. They all knew of the example made of the city of Alexandria when in 1882, this other Eastern City was bombarded for six hours without pause by the Imperial Navy. There may even been a few grizzled veterans among the Sultans' foreign artillery men who had seen action against the British in that battle some 14 years earlier.

Alexandria had then been a hotbed of Egyptian nationalism and a center of resistance to a Puppet Government installed by the British. When the nationalists seized control of the city nineteen British warships opened fire. The willingness of British ships to fire on densely populated cities was never again in doubt in this part of the world.

The Zanzibari knew full well what their defiant stance might cost them,but still they waited. Not one person abandoned the now fortified Palace.

As night fell Khalid went out to a public Mosque to pray and to show he was not afraid to walk the streets. Then as the night deepened an eerie silence fell over the City. Some witnesses said that "never had they know a quieter night." Another wrote that "the silence was deep and uncanny.....The noises of the endless shuffle of feet and the clattering and rustling made by thousands of human beings as they eat, work, play and move about: all these were stilled, as though the town was breathless with fear and tension."

The Battle:

The morning of the 27thwas clear and grew hot early as Citizens assembled on the roof tops to see what would happen. The Zanzibari leaders again sent a letter to the Americans asking that they forward a telegraph to London. The American representative refused, saying that "as Khalid had not been recognized as Sultan by the protecting power, neither could he be by me." With such diplomatic language was the last lost chance for peace disposed of.

The American counsel was most likely selected for this intermediary role by the Zanzibari because the USA was not one of the nations "given" parts of East Africa at the infamous Berlin Conference of 1885. However the American officials refused to transmit messages or in any real way dispute the right of a "protecting power" to protect the indigenous people to death. This was indeed a black day for diplomacy.

The British ultimatum had set 9:00 am as the time for the war to begin; the Navy

would open fire if the forces at the Palace did not surrender by then. Just

before that hour arrived a courageous scene occurred. A small launch left the Zanzibari compound and rowed slowly pastthree of the British ships. Its

mission was to deliver the Sultans' Captain to his only armed vesselthe H.H.S. Glasgow. That small wooden war yacht was surrounded by 5 armored giants

but the men on board had made no move to hoist anchor and escape. When the

Captain arrived they solemnly began the final preparations needed to fire their

elderly muzzle loading cannon and aimed them towards the two closest British ships. The British saw by this

act of defiance that no flag would be lowered by the Zanzibari that morning.

The Imperial British Fleet fired first, precisely on time and directly at the massed Zanzibari men on shore, the Zanzibari immediately fired back. At 9:05, despite it's impossible position, the H.H.S. Glasgow opened fire on the enemy. The British then directed heavy fire from both sides onto the Glasgow. Holed near the waterline she immediatelystarted to settle by the stern, firing all the time as she slid lower into the water.

Most Spectators fled the rooftops as misdirected shells landed well beyond the fortified compound, setting fires in several places within the City. Those observers left aloft could, for a short time, see the smoke from the guns on both sides firing but soon more smoke from fires touched off by explosions, obliterated the palace compound from view. Still the British ships fired on. It has been estimated that close to a thousand shells were fired into Zanzibar city that day. If true that means a shell landed about every three seconds for the best part of an hour.

Because of the obscured view most first-hand accounts focus more on the sounds of the battle rather than it's sights. One witness tells us that "for forty-five minutes the awful noise continued: dull roars, punctuated with the crack crack of the maxims and the snap of one-pounders, the shells shrieking through the air with splinters of them dropping about in an indiscriminate manner."

By 9:30 the brave Glasgowwas silent, all guns destroyed and many of

the crew dead or injured. The ship settled gently to the shallow seabed, its'

masts still showing above the waterline. The fire from the Zanzibari on shore had slackened, as one

outclassed gun after another was put out of action. The British fire too seem to

lessen as gunners sought targets in vain amidst the smoke and

officers began to look for some sign of surrender. Inside the compound it could

be seen that the Harem building was burning fiercely as were the warehouses next

to the water. Then a breeze blew the smoke aside for a moment allowing a clear

view of the large Palace flagstaff; with the bright red flag of Zanzibar still

flying. The British renewed their shelling with new zeal and again the scene was

soon shrouded in smoke.

The ship settled gently to the shallow seabed, its'

masts still showing above the waterline. The fire from the Zanzibari on shore had slackened, as one

outclassed gun after another was put out of action. The British fire too seem to

lessen as gunners sought targets in vain amidst the smoke and

officers began to look for some sign of surrender. Inside the compound it could

be seen that the Harem building was burning fiercely as were the warehouses next

to the water. Then a breeze blew the smoke aside for a moment allowing a clear

view of the large Palace flagstaff; with the bright red flag of Zanzibar still

flying. The British renewed their shelling with new zeal and again the scene was

soon shrouded in smoke.

After another 15 minutes of Bombardment the defensive fire from the shore had

completely ceased. All Zanzibari guns were out of action. The British firing

slowed and again the flagstaff came into view. The top was missing, the flag

shot away. Admiral Rawlins, in charge of the Naval squadron, took this to mean

surrender and ordered his ships to cease fire. The Marines were then ordered in,

to seize the remains of palace at bayonet point.

After another 15 minutes of Bombardment the defensive fire from the shore had

completely ceased. All Zanzibari guns were out of action. The British firing

slowed and again the flagstaff came into view. The top was missing, the flag

shot away. Admiral Rawlins, in charge of the Naval squadron, took this to mean

surrender and ordered his ships to cease fire. The Marines were then ordered in,

to seize the remains of palace at bayonet point.

A somewhat fictional account of this final action was provided by a Englishman writing only a year after the battle.

"Right gallantly the Askaris and Zanzibaris who man the guns of the usurper stick to their task, and blaze away at the mailed sides of the gunboats without producing the faintest impression, until one by one the field pieces are dismounted or scattered in fragments."

"From behind each sheltering ironclad heavily laden boats shoot out...but the landing of the blue-jackets is not to be entirely without argument on the other side. Here and there a gun cracks, and while most of the leaden pellets splash harmlessly in the blue water of the harbor, a few find lodgment amoung the occupants the boats."

The Aftermath:

With all but their handguns destroyed and with British marines coming ashore in the hundreds, Khalid finally gave the order to abandon the field of battle. Leaving 500 men dead in and around the Palace, the Sultan encouraged his Zanzibari irregulars to take the wounded and melt back into the city from whence they came. He then lead his remaining men including the surviving palace guard, on a dangerous march through the citytowards the German Embassy. (And towards the Loyalist troops who had still not been allowed to leave their defensive positions.)

A witness who was near the diplomatic quarter describes this scene: "What was my utter astonishment when I reached the consulate to see a large number of Arabs and their followers, headed by Khalid, all of them covered with dust and blood, coming toward me and making for the German consulate." Khalid bluffed his way past one group of British marines, who did not recognize him, and reachedthe sanctuary of the consulate. The Germans there had their own reasons for helping an opponent of the British and they welcomed him and a small number of senior companions. His soldiers were then disarmed (and their weapons looted) but then they were able to fade into the interior of the island while the government troops and British marines were distracted by the need to control the fires thatthreatened to envelop the city and also to deal with riots that broke out once the outcome of the battle became known.

Sayyid Khalid remained for 36 days a guest at the German Consulate. The British

demanded he be turned over

to them and surrounded the consulate with agents and soldiers so that he could

not escape. After weeks of diplomatic wrangling between the two European powers

on Oct. 2nd, the morning of an especially high tide when the sea lapped up against the

wall of the German building, Khalid stepped directly from the German consulate to a

small boat, never touching British controlled soil.

Sayyid Khalid remained for 36 days a guest at the German Consulate. The British

demanded he be turned over

to them and surrounded the consulate with agents and soldiers so that he could

not escape. After weeks of diplomatic wrangling between the two European powers

on Oct. 2nd, the morning of an especially high tide when the sea lapped up against the

wall of the German building, Khalid stepped directly from the German consulate to a

small boat, never touching British controlled soil.

From there he was conveyed to Dar es Salaam where he lived as a Prince in exile

for more than 15 years when WW1 brought

him again into conflict with the British Empire. That story will be continued

later as

part two of this unofficial Military History of Zanzibar.

From there he was conveyed to Dar es Salaam where he lived as a Prince in exile

for more than 15 years when WW1 brought

him again into conflict with the British Empire. That story will be continued

later as

part two of this unofficial Military History of Zanzibar.

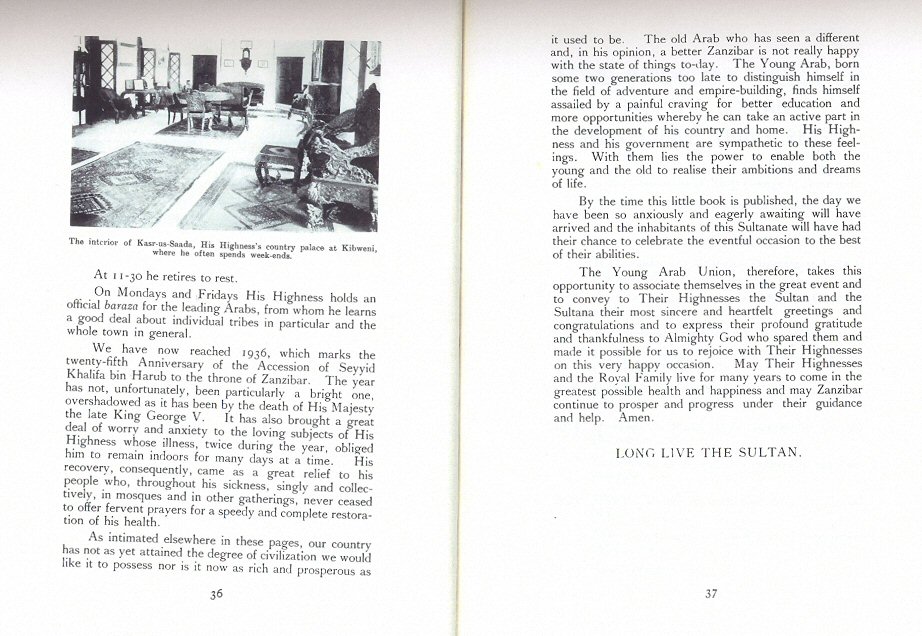

As for the damaged city, the palace was destroyed completely and never rebuilt.

The Harem building was also destroyed but a truncated replacement building was

soon put up. The damage to the lighthouse in front of the House of Wonders was

irreparable but the Beit el Ajaib (H. of W.) itself was not fatally damaged and so

a new lighthouse attachment was added to that Palace when it was repaired in

1899. By the early 1900's the square was once again ready to hostpublic

events.

As for the damaged city, the palace was destroyed completely and never rebuilt.

The Harem building was also destroyed but a truncated replacement building was

soon put up. The damage to the lighthouse in front of the House of Wonders was

irreparable but the Beit el Ajaib (H. of W.) itself was not fatally damaged and so

a new lighthouse attachment was added to that Palace when it was repaired in

1899. By the early 1900's the square was once again ready to hostpublic

events.

The British popular Press reported the battle in some detail at the time and even in the USA it was under study. Near the end of 1896 the magazine "Scientific American" analyzed the mechanics of the bombardment. With a chilling foretaste of possible dangers to come, dangers that World War I soon made too real, the Americans attempted to apply the lessons learned in Zanzibar to their own long coastline.

"The 6 inch rapid fire gun on the Royal Arthur, a sister ship to the St. George (the British flagship during the Zanzibari war)... has a record of eighteen aimed shots in three minutes. If this rate of fire of six shots a minute could be maintained for the thirty-seven minutes (the assumed length of the war)... one rapid fire gun would in the time throw 222 explosive shells, weighing 100 pounds apiece into a city. The St. George carries 5 such guns on her broadside...In addition she could deliver (in that time) some 120 huge shells, weighing 320 pounds apiece, from her 9.2 inch heavy guns.

The type of ship that knocked the Zanzibar buildings to pieces in less than an hour is possessed by every state that owns a navy, big or little. To those people who cannot see the necessity for our ever recurring sea coast defense, this fact... should prove a convincing argument."

An Alamo in Africa

Zanzibar Courage seems a particular kind of bravery, centered of a strong

sense of justice, and a principled stubbornness of character.These traits,

coupled with the long standingpolitical literacy of the people of

Zanzibar, have often frustrated the plans of would be Rulers who attempted to

dominate the Islands without due regard to the interests of the

people.

Zanzibar Courage seems a particular kind of bravery, centered of a strong

sense of justice, and a principled stubbornness of character.These traits,

coupled with the long standingpolitical literacy of the people of

Zanzibar, have often frustrated the plans of would be Rulers who attempted to

dominate the Islands without due regard to the interests of the

people.

It has been said that the shortest war was similar to the American Revolution of 1776. In both wars patriots challenged the right of the British Empire to rule without allowing for adequate local control of the indigenous social and economic systems. However the 1896 Anglo/Zanzibari war, consisting of just one battle, is perhaps better likened to the famous American battle at the Alamo. In both, the story of the battle has become more important than the actual tactical outcomes.

In that case a small band of Texas patriots occupied a fortified position and faced down the massed guns of a much more powerful Mexican army without flinching. Because of their attachment to the principles of independence and self determination they became national heroes.

In the 1896 war a band of patriotic Zanzibari faced down the massed guns of a British fleet and many of them died rather than give up their cause.Theirs is a story that should not be forgotten.

Their example is also a message to ponder even today, when at times Zanzibaris fight Zanzibaris and powerful national and international forces compete to dominate the area. Without listening closely to the voices of the people of these islands will we see another Alamo in Africa?

Click here for Sources and Bibliography

coming soon:

Zanzibar in the Great War: 1914-16

By Torrence Royer. 2002.

All rights reserved.

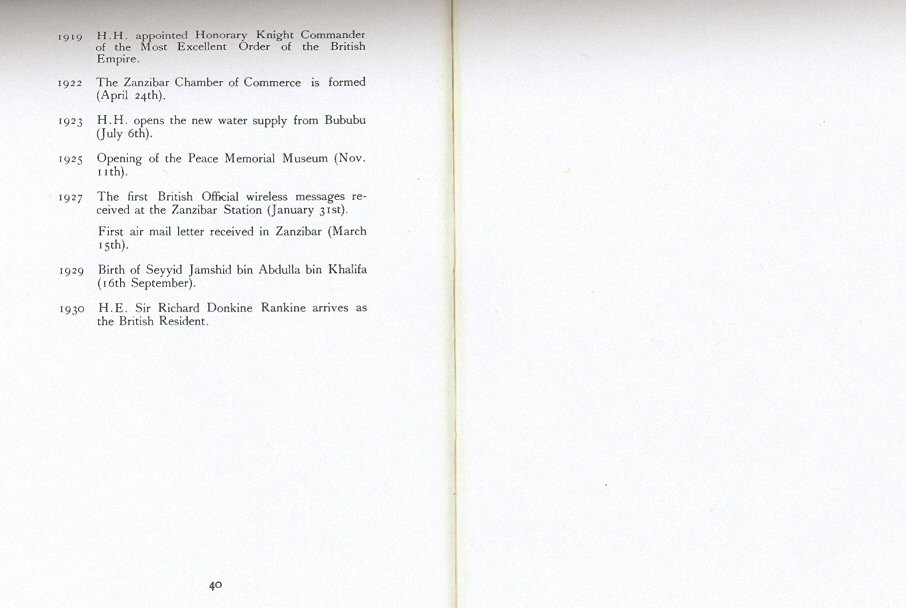

Barghash@msn.com